November 27, 2025, the peer‑review ecosystem for machine learning hit a wall.

A subtle bug in OpenReview’s API briefly exposed one of the most sensitive parts of the research process, reviewer anonymity, making it accessible to anyone with a browser. Within hours, researchers discovered they could query an internal profile‑search endpoint and reveal the identities of authors, reviewers, and area chairs for major venues, including ICLR 2026, ACL ARR, NeurIPS, ICML, EMNLP, and various specialized workshops and symposia.

Social media lit up. Memes flew. Some people treated it like long‑overdue karma for bad reviews. Others saw it for what it is: a serious security and governance failure in the infrastructure that underpins modern ML research.

This article walks through the incident in detail, using only public, verifiable information and official statements. We will reconstruct the timeline, analyze the technical cause, and unpack what this means for conferences, reviewers, and anyone building systems that handle sensitive data.

Throughout the journey, we’ll examine community reactions and explore what a more resilient future for peer review could entail.

1. What Was the OpenReview / ICLR 2026 Leak?

The incident centers on OpenReview, the platform used by many top conferences (ICLR, NeurIPS, ICML, ACL, CVPR, and others) to manage submissions and peer review.

On November 27, 2025, the ICLR 2026 organizers published an official statement confirming that:

“ICLR was made aware of a software bug that leaked the names of authors, reviewers, and area chairs. The bug impacted all conferences hosted on OpenReview…”

In parallel, OpenReview issued its own “Statement Regarding API Security Incident – November 27, 2025”, where the team described the core issue:

“…a security vulnerability in our API that allowed unauthorized access to the identities of normally anonymous roles (reviewers, authors, and area chairs) across venues through a specific profile search API endpoint.”

The key facts from these two statements are:

- The leak affected “all conferences hosted on OpenReview”, not just ICLR.

- The exposed data concerned the identities of roles that are typically anonymous: reviewers and area chairs, plus author identities in blind phases.

- The root cause was a bug in a profile search API endpoint that failed to handle authorization checks properly.

This aligns with independent community reports. A widely shared Reddit thread titled “[D] Openreview All Information Leaks” described how “all authors, reviewers, ACs are revealed,” and noted that the bug had been fixed soon after discovery (r/MachineLearning).

Around the same time, another now‑deleted post on r/PhD documented example API calls to:

- https://api2.openreview.net/profiles/search?group=ICLR.cc/2026/Conference/Submission{}/Authors

- https://api2.openreview.net/profiles/search?group=ICLR.cc/2026/Conference/Submission{}/Reviewer_{}

- https://api2.openreview.net/profiles/search?group=aclweb.org/ACL/ARR/2025/October/Submission{}/Reviewer_{}

Those URLs, preserved in search snippets, make it clear that the vulnerable endpoint was profiles/search and that the attack surface was the group parameter, which allowed callers to enumerate identities for specific conference roles.

In other words: a read‑only enumeration API, intended for privileged users, was exposed to the entire internet.

2. A Precise Timeline of the Incident

OpenReview’s own statement provides an unusually detailed response log. From that document, we can reconstruct the day:

- Statement Regarding API Security Incident – November 27, 2025

- 10:09 AM EST – Issue reported by ICLR 2026 Workflow Chair to OpenReview.

- 10:12 AM – OpenReview acknowledged the report and began an investigation.

- 11:00 AM – Fix deployed to

api.openreview.net. - 11:08 AM – Fix deployed to

api2.openreview.net. - 11:10 AM – Program chairs and workflow chair notified of resolution.

So the initial patch went live within about one hour of the first report.

OpenReview further clarified that: “The vulnerability allowed queries to the profiles/search endpoint using the group parameter in an unintended fashion to return identity information without proper authorization checks.”

After patching, they started:

- Analyzing API logs to understand which accounts accessed sensitive data, especially at a large scale.

- Preparing to notify all “deanonymized” users by email.

- Planning additional public reports about the incident.

They also committed to contacting multi‑national law enforcement agencies if they found evidence of malicious exploitation—a reminder that this is not just an academic embarrassment but a potential legal issue in jurisdictions with strong data‑protection laws.

ICLR’s own statement, sent to the community and posted on their channels, focused on consequences within the conference:

“Any use, exploitation, or sharing of the leaked information… is a violation of the ICLR code of conduct, and will immediately result in desk rejection of all submissions and multi‑year bans from the ICLR conference.” And later:

“Doxxing, harassment, or any form of retaliation (whether online or in person) will not be tolerated and will result in the maximum penalties defined by the Code of Conduct.”

In short:

- Timeline: Bug disclosed → patch rolled out within ~1 hour → public statements same day.

- Scope: All conferences hosted on OpenReview; all anonymous roles potentially exposed.

- Immediate response: Technical fix plus strong policy language from both OpenReview and ICLR.

For readers who want to understand typical expectations around coordinated vulnerability disclosure in research infrastructure, the OpenReview FAQ includes a section on how to report vulnerabilities and bugs (OpenReview FAQ). Still, this incident goes far beyond a routine bug report.

3. What Exactly Leaked?

Neither ICLR nor OpenReview list every data field that may have been exposed. However, combining official statements, API snippets, and OpenReview’s data model, we can infer the following:

3.1 Identities of anonymous roles

The most critical leak is the mapping between people and their roles in specific conferences:

- Which profiles belong to reviewers of a given submission set?

- Which profiles belong to area chairs?

- In some phases, which profiles correspond to blind authors?

OpenReview explicitly describes these roles and their intended anonymity in its documentation for conferences and reviewers (OpenReview Getting Started). The entire double‑blind review process is predicated on the assumption that:

- Reviewers do not know which authors wrote a paper (at least initially).

- Authors do not know who reviewed or chaired their paper.

- Third parties cannot trivially deanonymize the review graph.

The bug broke that assumption.

3.2 Profile metadata

Each OpenReview profile can include:

- Name

- Institutional affiliation and country

- Email domains (often partially visible even in limited mode)

- External links (DBLP, Google Scholar, personal homepage)

- Education and employment history

- Declared conflicts and collaborators

You can see a complete description of typical profile fields in conference guides, such as CVPR’s instructions for completing your OpenReview profile (CVPR 2025 Guide).

The compromised endpoint appears to have returned enough information to uniquely identify individuals—even if some fields were notionally “limited”. Pairing this with the group‑level mapping (“Reviewer for ICLR 2026”, “Area Chair for ARR October 2025”) greatly amplifies the privacy impact.

3.3 What (probably) was not leaked

There is no indication in any official statement that the bug was exposed:

- Passwords or authentication tokens.

- Private messages.

- Full submission content beyond what was already visible via normal permissions.

The incident is therefore best understood as a mass deanonymization rather than a full account compromise.

From a security classification standpoint, this is still serious: identity metadata combined with behavioral data (reviews, scores, decisions) can cause real harm even without password leakage.

4. Enforcement, Retaliation, and the Human Side

Both ICLR and OpenReview emphasize that the use of leaked information is itself a violation.

OpenReview’s statement ties this to their Terms of Use (OpenReview Terms) and spells out the consequences:

“Any use, exploitation, or sharing of the leaked information is a violation of OpenReview’s Terms of Use and may result in OpenReview account suspension… Doxxing, harassment, or any form of retaliation… will not be tolerated, and will result in maximum penalties…”

ICLR’s organizers go even further, promising immediate desk rejection of all submissions and multi‑year bans for offenders.

This is not hypothetical. Within hours of the leak, social media was already full of jokes, anger, and calls for revenge.

This meme captures the unstable triangle that emerges when everyone can see who rejected whom. The anonymity buffer that normally absorbs disappointment is suddenly gone.

These jokes are funny because they land close to the genuine frustration many researchers feel about opaque or low‑quality reviews. But in a context where real people’s names are suddenly linked to previously anonymous decisions, the boundary between humor and harassment can disappear quickly.

ICLR’s statement directly addresses this risk:

“Doxxing, harassment, or any form of retaliation (whether online or in person) will not be tolerated…”

For conferences, the challenge now is not only technical remediation but also rebuilding trust among reviewers who reasonably worry about their safety and career consequences.

5. How the Community Is Reframing Anonymity

Beyond outrage and memes, the incident has triggered a deeper conversation about how peer review should work.

One widely shared post by researcher Jiaxuan You framed the ICLR leak as an opportunity to rethink incentives:

The core argument:

- ICLR has historically maintained paper quality partly because rejected papers were public, creating a reputational check on authors.

- Reviewers, by contrast, operate under a stronger veil of anonymity—even when delivering “fundamentally irresponsible” reviews.

- Perhaps anonymity should be conditional:

- Good‑faith, careful reviews remain anonymous (if the reviewer wishes).

- Persistently irresponsible reviewers lose that anonymity after confirmation by the program committee.

This is an extreme position in the context of a fresh leak, but it reflects a long‑running tension:

- Anonymity protects reviewers from retaliation and allows them to be frank.

- Too much opacity enables neglect, abuse of power, and low effort.

The OpenReview platform was initially designed to increase transparency—through open discussion, public comments, and the archiving of reviews—while still preserving formal anonymity. That balance is now under renewed scrutiny.

For further background on longstanding debates about peer review transparency, see overviews and community discussions such as “Why do authors nuke their OpenReview discussions after paper is accepted?” on r/MachineLearning.

6. Technical Lessons from the profiles/search Bug

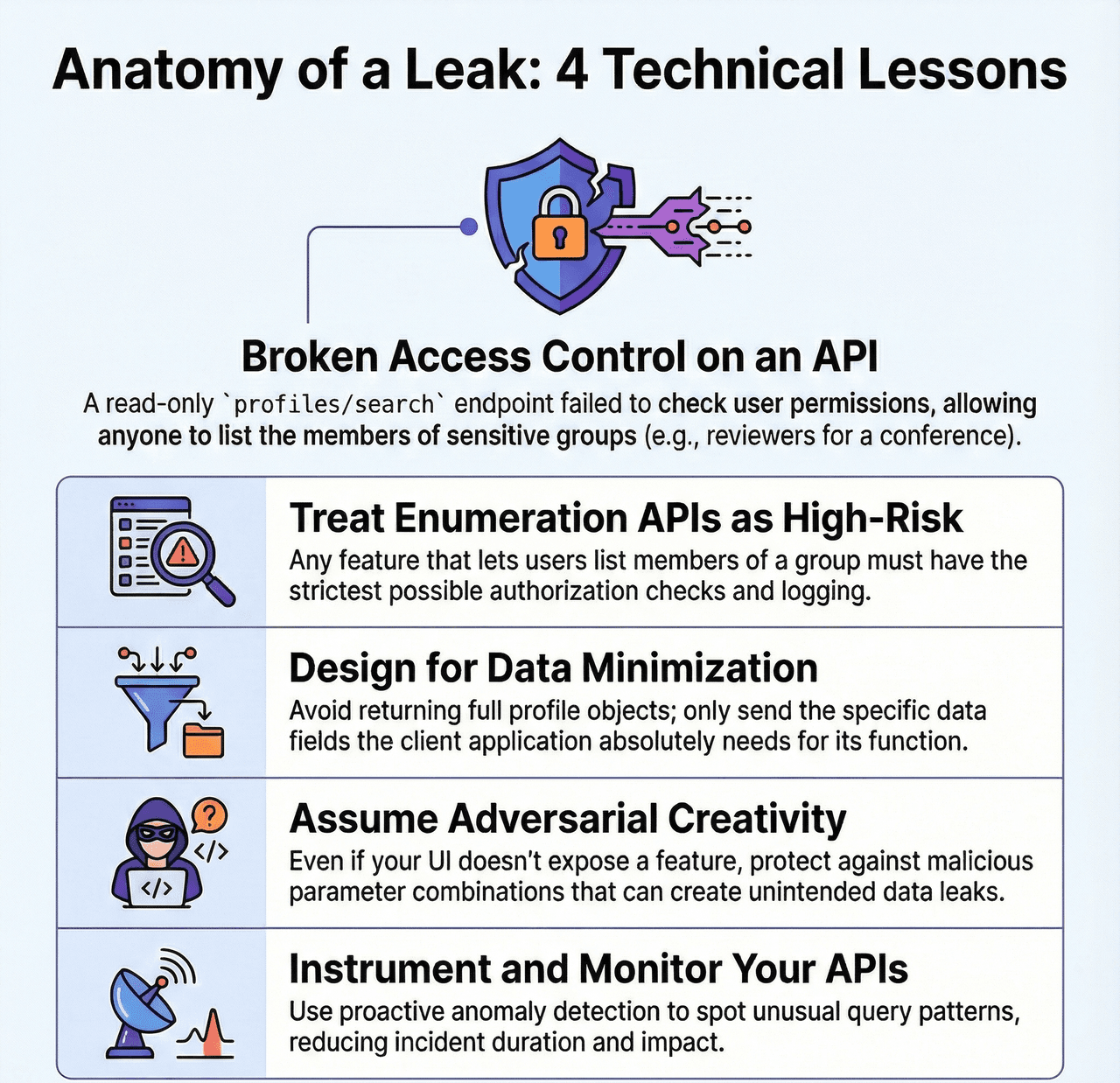

From an engineering standpoint, the leak was caused by a specific failure mode: authorization on a high‑power enumeration API.

OpenReview’s statement explicitly mentions:

“queries to the profiles/search endpoint using the

groupparameter in an unintended fashion… without proper authorization checks.”

This is a textbook example of what security literature describes as Broken Access Control—currently ranked as the top web application vulnerability category by the OWASP Top 10.

What makes this case instructive is that:

- The endpoint itself is legitimate and necessary for the system’s internal workflows. You cannot simply delete it.

- It exposes metadata that may look harmless in isolation but becomes dangerous when paired with group semantics (“Reviewer for ICLR 2026”).

- The surface area is “read‑only”, which can make it easy to underestimate its risk during design reviews.

Practical takeaways for anyone building research infrastructure or multi‑tenant SaaS:

- Treat enumeration APIs as high‑risk. Any endpoint that lets callers iterate over users, roles, or group membership should require the strictest possible authorization checks and logging.

- Design for minimization. Avoid returning more fields than absolutely necessary. If the caller only needs IDs, do not return complete profile objects.

- Assume adversarial creativity. Even if no UI exposes a feature, parameter combinations (like the

groupargument here) can create unintended information channels. - Instrument and monitor. OpenReview now has to analyze large volumes of API logs retroactively. Proactive anomaly detection on unusual query patterns could reduce both incident duration and impact.

For a more general treatment of leakage risks in AI systems, see works such as “Breach By A Thousand Leaks: Unsafe Information Leakage in ‘Safe’ AI Responses” presented at ICLR 2025 (OpenReview paper). While that work focuses on model outputs rather than platform metadata, the underlying theme is the same: small, individually “safe” disclosures can aggregate into serious leaks.

7. Governance, Law Enforcement, and Responsibility

One of the most striking lines in OpenReview’s incident statement is the promise to involve law enforcement:

“We will be contacting multi-national law enforcement agencies about consequences for this behavior.”

This highlights several governance layers:

- Platform terms of use. OpenReview’s legal terms explicitly forbid both circumvention of intended data access rules and the sharing of information about discovered bugs without responsible disclosure (OpenReview Terms).

- Conference codes of conduct. ICLR layers its own sanctions—desk rejection and multi‑year bans—on top of platform‑level account suspension.

- National and regional regulation. Many reviewers and authors are based in jurisdictions covered by GDPR or similar data‑protection laws, under which mishandling identifiable data can carry regulatory penalties.

The interplay between these layers is still evolving. But the direction is clear:

- Platforms like OpenReview are no longer just community tools; they are critical infrastructure.

- The expectation is moving toward professional‑grade security, formal incident handling, and transparent post‑mortems.

For organizations that depend on third‑party platforms for sensitive workflows—whether academic, corporate, or governmental—this incident is a reminder that vendor risk is system risk.

8. How Should Authors and Reviewers Respond?

If you have served as an author, reviewer, or area chair on OpenReview in the last few years, what should you actually do?

8.1 Short‑term steps

-

Watch for official notifications. OpenReview has committed to emailing all users whose anonymity may have been compromised. Make sure mail from

openreview.netis not trapped in spam. -

Be cautious with public commentary. Even if you are angry about past reviews, resist the temptation to “name and shame” reviewers based on leaked data. Doing so not only violates codes of conduct but may also put you on the wrong side of legal and professional boundaries.

-

Report harassment or misuse.

- ICLR asks participants to report incidents to

[email protected]. - OpenReview directs users to

[email protected]for security issues and[email protected]for policy concerns (emails listed in their statement and policy page).

- Secure your own accounts. Even if credentials were not leaked, this is a good moment to ensure that:

- You use unique passwords.

- You enable two‑factor authentication where available.

- You do not reuse your OpenReview password on other services.

8.2 Longer‑term mindset shifts

For reviewers and ACs:

- Recognize that absolute anonymity is now more fragile than many assumed. Write reviews that you would be willing to defend in a room of peers, even if names are not supposed to be visible.

- At the same time, push conferences and platforms to improve protections, not abandon anonymity wholesale.

For authors:

- Use this opportunity to promote improved review quality measures, such as structured rubrics and accountability for clearly negligent reviews, instead of resorting to personal retaliation.

- Be aware that some of your own blind submissions may have been deanonymized in logs or by third parties. Factor this into decisions about cross‑submission, public arXiv posting, or sensitive collaborations.

For institutions and labs:

- Treat participation in large conferences as an information‑risk vector. Create basic internal guidance for staff on what to do in events like this—similar to how many organizations already handle data breaches by cloud vendors.

9. What This Means for the Future of Peer Review

The OpenReview / ICLR 2026 leak is not “just another bug.” It exposes structural tensions in how the research community manages trust:

-

Centralization vs. Resilience. Concentrating peer review across dozens of top conferences into a single platform offers significant benefits in consistency and tooling, but it also creates a single point of failure.

-

Transparency vs. Safety. OpenReview was built to make reviews more visible and discussions more open. Without careful design, that same visibility can undermine privacy and chill participation.

-

Human frustration vs. institutional responsibility. Many of the memes you shared—joking that OpenReview has turned into “OpenReviewer,” or showing authors, reviewers, and meta‑reviewers in a three‑way standoff—are rooted in real dissatisfaction with how arbitrary the process can feel. But platform bugs are the wrong way to “fix” that.

If there is a constructive lesson here, it is that technical security and social governance cannot be separated:

- You cannot fix a broken culture of reviewing just by doxxing bad reviewers.

- You also cannot demand reviewer labor at scale while treating their privacy as an afterthought.

The incident may ultimately accelerate:

- Stronger security engineering practices for academic infrastructure.

- More explicit norms and consequences for irresponsible reviewing—defined and enforced by program committees, not by mob‑driven exposure.

- More experimentation with alternative review models that rebalance transparency, accountability, and safety.

For now, though, the priority is straightforward: contain the damage, support the people whose anonymity was compromised, and rebuild trust in the systems that research depends on.

Posts

Posts